Musical artists turn to old tech for vintage sound

John Mellencamp’s recent album “No Better Than This” was recorded by the singer and “O Brother, Where Art Thou” music producer T-Bone Burnett using a single vintage RCA 77DX microphone and a 50-year-old refurbished mono Ampex 601 portable tape deck.It’s easy to dismiss the record as simply an artful manifesto on Mellencamp’s part — he along with fellow music artists Prince and Stevie Nicks have all railed publicly that digital technology in general and the Internet in particular have destroyed both music and the music business. Except that Mellencamp also took what has become a recent trend to its extreme: as CD sales continue to plummet and digital downloads barely dent that fiscal void, new recordings using hoary analog technology and released on vinyl making a surprising comeback.Vinyl’s resurgence has been well documented. In 2009, 2.5 million vinyl albums were purchased, up 33% from the previous year and showing a sustainable rise from sales of 858,000 in 2006, according to Nielsen SoundScan. And new LP prices can range as high as $30, twice what the typical new CD fetches.But as vinyl records grow in popularity, the back-to-analog effect has been heading upstream — more artists now choosing to record their LPs from the very first note using ancient tape machines revived by artisans with soldering irons. Taylor Swift, Jack White, the Secret Sisters, Lenny Kravitz, and Elton John and Leon Russell on their recent “Reunion” LP are among analog’s fanatics; Kravitz owns one of the four-track tape decks used to record the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s” album at Abbey Road Studios.Mike Spitz, owner of both ATR Services, which is refurbishing vintage analog decks, and ATR Magnetics, which is manufacturing tape for them, says business has boomed in recent months. “Tape is now the holy grail for musicians,” he says, welcomed by both industry veterans who miss the format’s sine-wave warmth and by indie twentysomethings who are experiencing full bandwidth after a lifetime of listening to highly compressed MP3s.Nathan Chapman, Swift’s record producer, says the 21-year-old loves the sound of analog tape as well as the way it changes the recording process. “Taylor’s young and she has the energy to go the extra mile it takes to record in analog’s more limited number of tracks,” Chapman says. “A lot of older recording artists have gotten used to the convenience of digital.“It also affects her vocals, in a good way. When recording vocals to Pro Tools there’s always a tiny bit of latency, for the analog-to-digital conversion process. Recording directly to tape, there’s an immediacy Taylor hears and reacts to.”A vintage multitrack deck like a Studer A827 costs $7,000 or more, and and additional $10,000 to refurbish, but Spitz says demand continues to increase. The cost of the media is also rising — a reel of 2-inch tape today costs $250 to $300, more than double the cost a decade ago. That reflects the scarcity of the necessary raw materials like base film and oxide, says Don Morris, director of sales for RMG Intl., the Dutch company that took over the assets of BASF’s liquidated EMTEC tape manufacturing business. “But musicians are willing to pay that now, because they know how much better it sounds,” he says.

A recent innovation that addresses tape cost is Clasp — the Closed Loop Analog Signal Processor developed by Nashville-based Endless Analog. The $10,000 unit is essentially an analog front end to a digital audio workstation like Pro Tools, imparting analog’s warmth and the tonality associated with running the tape at various speeds — slower speeds like 7.5 inches per second are used to capture the low frequencies of drums and bass while vocals and guitars sparkle at 15 and 30 ips.

Clasp’s inventor, Chris Estes, says since the tape is used for processing the sound but not to store it, one reel of 2-inch tape can theoretically be used as many as 10,000 times, mitigating the high cost of the media. “The tape is constantly running, not being constantly stopped and restarted, which stresses and stretches the tape,” he says.Perry Margouleff, who owns the vintage-equipment fantasy land Pie Studios in Glen Cove, N.Y., which attracts artists like the Rolling Stones and Jimmy Page, says working in analog restores some of the talent filtering lost to the DIY ease of digital recording. “When you record in analog, the drummer has to play in time, the singer has to sing in tune, the guitar player has to nail the part, because you can’t go back later and fix it with a black box,” he says.Analog-recorded music is finding its way into films. Soul singer Sharon Jones’ rendition of 2009′s “Up in the Air” theme track “This Land Is Your Land” was recorded in the funky and analog Daptones Records studio in Brooklyn’s Bushwick section, where the basic tracks for Amy Winehouse’s Grammy-winning “Rehab” were also recorded.“The sound of the tape is a big part of the sound of the record,” says Gabriel Roth, Jones’ record producer and Daptone partner.Analog’s attraction lies in its ultra-high resolution capability, Spitz explains. Direct Stream Digital (DSD), the high-resolution digital disc format Sony used for its audiophile SACD format, is capable of 2.884,000 transitions per track per second, but a high-quality mastering tape contains approximately 80 million transitions per track second. “And that’s just for 1/4-inch two-track tape running at 15 IPS,” says Spitz. “The resolution goes up substantially with wider tracks and higher (tape) speeds.”However, don’t pull your tie-dyed jeans out the closet just yet, say musicians, producers and music execs. The entire infrastructure of professional music recording has been firmly entrenched in the nonlinear digital domain for more than a decade, and even basic tape deck maintenance such as headstack alignment is no longer part of the core curricula for aspiring engineers at media academies such as Full Sail U., SAE and Berklee College of Music.“Analog is great, but it’s just economically unrealistic to think you can use it all the time or even very often,” says David Frangioni, who has cut tracks for Aerosmith, Bryan Adams, Ricky Martin and Ozzy Osbourne. Aside from the cost of media and hardware, Frangioni says contemporary records need to have access to more tracks and nonlinear editing capabilities to be competitive on radio and at retail. “These days especially, you have to balance time and budget against the cost of analog.”Michael Lloyd, a record producer and exec at Curb Records in L.A., says while the cost of tape media may not be a budget-breaker for major labels, he wonders, at a time when music sales continue to decline, if recording technology even matters to consumers. “At the end of the day, it all goes out (on CD) or MP3. I’d rather see the concentration on good songs than on the technology. We have a good digital workflow in place.”Analog recording is expensive and exotic compared to digital systems and it will remain a niche. But its renewed popularity suggests some listeners may be tired of MP3′s squeezed sonics.

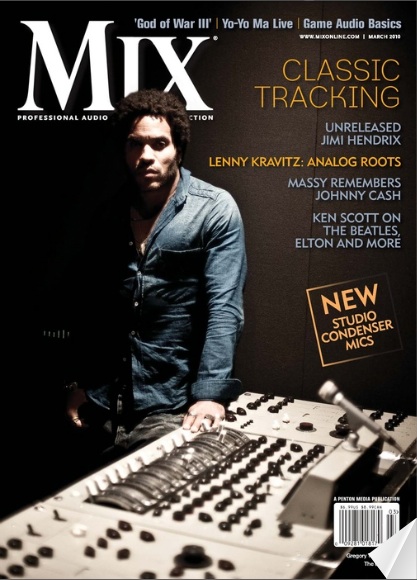

Lenny Kravitz’s personal studio is built 100 feet from the beach on eleuthera Island in the Bahamas, a 110-mile- long sliver of land 50 miles east of nassau. “I’ve always loved my roots,” says Kravitz. “My grandfather was born on an island called Ingua, the most southern Bahamian island closest to cuba. My parents used to send me down here for summers;we’d come here for christmas and holidays.” as if locating the studio in a caribbean para- dise wasn’t enough, Kravitz stocked it with a

dream collection of gear collected throughout

his career. From the start, Kravitz always knew

the sound he was going for, which started his

analog love affair. “I started recording at [henry

hirsch’s] waterfront in 1985 or ’86, and I knew I

wanted to make a certain kind of record,” Krav-

itz remembers. “I saw the way technology was

going in the late ’80s. records were sounding

very processed—it was all about those big gated

drums and everything sounding unnatural; in

some cases, it was cool for different artists, but it

didn’t work for me. I knew I wanted an intimate-

sounding album.” Through his association with

hirsch over a number of albums, Kravitz would

be introduced to and then buy the gear that cre-

ated his desired sounds.

Gregory Town Sound started as a garage built

by Kravitz to protect some of his belongings dur-

ing hurricane season. It is a ranch-style concrete

structure poured in place with a cantilevered roof.

“It’s the most amazing studio that I’ve worked

in, and it has the gear I’ve been collecting for

20 years,” says Kravitz. “It’s an incredible place

to be creative.” also being an interior and furni-

ture designer, Kravitz started with an aesthetic in

mind and then brought in Miami-based acousti-

cian and designer ross alexander, who has been

doing studio integration and

design since 1981. “what I do

is put on paper what I want:

wood here, cork there, do this

and that,” says Kravitz. “Then

ross does his mathematical

measurements and tells me

what I can and cannot do.

From there, I can go forward

with that design or change out

a specific material so I’ll get the

sound I want.”

It’s the gear that shines at Gregory Town

Sound, where vintage signal flow is king. It starts

with an all-star array of mics from Schoeps, neu-

mann, coles, aea, Sennheiser, Telefunken, Shure,

aKG and more. all can be recorded through the

studio’s wrap-around helios console or an eMI-

designed reDD 37 once owned by abbey road

and used in Studio 1. “The helios was henry’s

choice,” says studio manager, gear and guitar

tech alex alvarez about hirsch’s positive influ-

ence in Kravitz’s gear-buying decisions.

“[Kravitz] purchased a helios and was trying

to go after more of a Stones and Zeppelin sound.

That started off around the Circus album when we

went that route.” after the Circus album, Kravitz

sold the console and bought a strawberry-red he-

lios from 10cc, which had some key components

missing and ended up being racked for optimal

use. Kravitz bought the current helios at Gregory

Town Sound from leon russell about seven years

ago. It sat for two years in a locker and then was

refitted by tech Dave amels before it came to the

Bahamas. The reDD 37 was purchased 18 years

ago by Kravitz, who was urged to make the leap

by hirsch. “Lenny had to take every dime he just

made,” says alvarez. “he hadn’t sold a million al-

bums yet and he took a chance at it.”

other vintage gear is housed in the racks and

includes eQ and dynamics processors from API,

Fairchild, eMI, rca, Universal audio and retro. (For

a complete list of lenny’s gear, visit mixonline.com.)

Speakers are ATC ScM200 aSl and B&w nautilus

805 monitors, among others. The studio also has a

collection of analog multitrack machines including

a Studer c37 2-track, a J37 4-track once owned by

abbey road, an 827a 24-track and an a-80 2-track,

as well as a 3M M79 with 16-track headstack. There

is also a Pro Tools system with apogee converters

clocked by antelope audio.

Lenny Kravitz’s personal studio is built 100 feet from the beach on eleuthera Island in the Bahamas, a 110-mile- long sliver of land 50 miles east of nassau. “I’ve always loved my roots,” says Kravitz. “My grandfather was born on an island called Ingua, the most southern Bahamian island closest to cuba. My parents used to send me down here for summers;we’d come here for christmas and holidays.” as if locating the studio in a caribbean para- dise wasn’t enough, Kravitz stocked it with a

dream collection of gear collected throughout

his career. From the start, Kravitz always knew

the sound he was going for, which started his

analog love affair. “I started recording at [henry

hirsch’s] waterfront in 1985 or ’86, and I knew I

wanted to make a certain kind of record,” Krav-

itz remembers. “I saw the way technology was

going in the late ’80s. records were sounding

very processed—it was all about those big gated

drums and everything sounding unnatural; in

some cases, it was cool for different artists, but it

didn’t work for me. I knew I wanted an intimate-

sounding album.” Through his association with

hirsch over a number of albums, Kravitz would

be introduced to and then buy the gear that cre-

ated his desired sounds.

Gregory Town Sound started as a garage built

by Kravitz to protect some of his belongings dur-

ing hurricane season. It is a ranch-style concrete

structure poured in place with a cantilevered roof.

“It’s the most amazing studio that I’ve worked

in, and it has the gear I’ve been collecting for

20 years,” says Kravitz. “It’s an incredible place

to be creative.” also being an interior and furni-

ture designer, Kravitz started with an aesthetic in

mind and then brought in Miami-based acousti-

cian and designer ross alexander, who has been

doing studio integration and

design since 1981. “what I do

is put on paper what I want:

wood here, cork there, do this

and that,” says Kravitz. “Then

ross does his mathematical

measurements and tells me

what I can and cannot do.

From there, I can go forward

with that design or change out

a specific material so I’ll get the

sound I want.”

It’s the gear that shines at Gregory Town

Sound, where vintage signal flow is king. It starts

with an all-star array of mics from Schoeps, neu-

mann, coles, aea, Sennheiser, Telefunken, Shure,

aKG and more. all can be recorded through the

studio’s wrap-around helios console or an eMI-

designed reDD 37 once owned by abbey road

and used in Studio 1. “The helios was henry’s

choice,” says studio manager, gear and guitar

tech alex alvarez about hirsch’s positive influ-

ence in Kravitz’s gear-buying decisions.

“[Kravitz] purchased a helios and was trying

to go after more of a Stones and Zeppelin sound.

That started off around the Circus album when we

went that route.” after the Circus album, Kravitz

sold the console and bought a strawberry-red he-

lios from 10cc, which had some key components

missing and ended up being racked for optimal

use. Kravitz bought the current helios at Gregory

Town Sound from leon russell about seven years

ago. It sat for two years in a locker and then was

refitted by tech Dave amels before it came to the

Bahamas. The reDD 37 was purchased 18 years

ago by Kravitz, who was urged to make the leap

by hirsch. “Lenny had to take every dime he just

made,” says alvarez. “he hadn’t sold a million al-

bums yet and he took a chance at it.”

other vintage gear is housed in the racks and

includes eQ and dynamics processors from API,

Fairchild, eMI, rca, Universal audio and retro. (For

a complete list of lenny’s gear, visit mixonline.com.)

Speakers are ATC ScM200 aSl and B&w nautilus

805 monitors, among others. The studio also has a

collection of analog multitrack machines including

a Studer c37 2-track, a J37 4-track once owned by

abbey road, an 827a 24-track and an a-80 2-track,

as well as a 3M M79 with 16-track headstack. There

is also a Pro Tools system with apogee converters

clocked by antelope audio.